chool North Italian

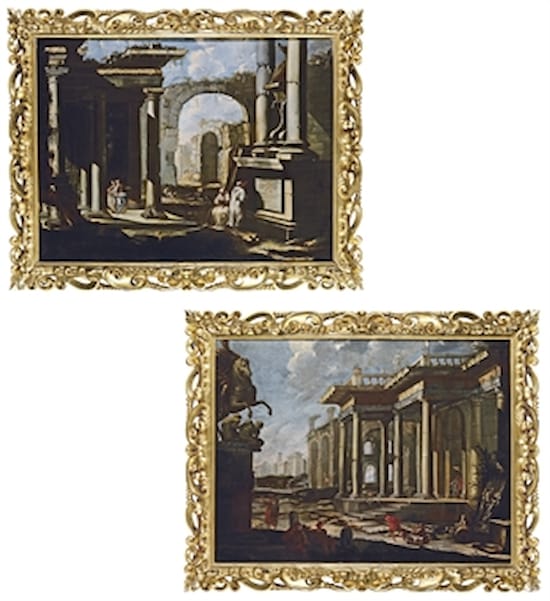

A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks & A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue

oil on canvas

123.8 x 162 cm (48¾ x 63¾ in)

a pair (2)

During the early part of the eighteenth century the capricci emerged as a mature art form, the architectural fantasy serving as an ideal creative outlet for artists. This pair of paintings is indicative of the genre during that period. A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks is a dramatic image of crumbling Doric architecture. Chipped columns rise up and out of the picture, dwarfing the figures below, and a huge archway frames the background. On the right-hand side there are two monks, one of whom is engrossed in a book whilst his companion reads the inscription of the monument under which they stand. On the right-hand side two figures in oriental dress are having an intense discussion. In the background an impoverished man, slumped asleep on the ground, is contrasted with a dashing horseman, who gallops out of sight. Our eye is led from figure to figure, as the painting recedes. They animate, and draw attention to, the architectural spaces which they occupy.

A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue is in a similar setting of Roman ruins, although in this work the composition is much more spacious, with a sense of openness and a deeper internal recession. On the left-hand side is a dramatic equestrian statue, which shows a horse rearing up on its hind legs as two kneeling figures cower below. Once again, contrasting figures are scattered throughout the scene. A man in a red tunic drags a cart through the ruins and in this cart sits a legless man; the scruffy poverty of this unusual pair is contrasted with the young, elegant and well-dressed couple who stand in the shadows of the building.

Both scenes are imbued with a heavy sense of decaying antiquity. The architecture is worn and chipped by the passing of time and in A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue the huge capital of a column lies forlornly on its side. In both paintings much of the neglected architecture is overgrown with creeping foliage and in the foreground of A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks, a gnarled tree grows amongst the ancient structures. This feeling is heightened by the classical dress of some of the figures detailed.

One of the most distinctive features of this pair is the dramatic use of chiaroscuro. Both paintings are lit by bright sunshine, which makes the contrasting shadow more intense. This is particularly notable in the case of A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks, where, on the right-hand side, a thick beam of shadow slices through the bright scene. The painting anticipates the dramatic swathes of light and dark that were to characterise the capricci of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), who fully realised the genre as a vehicle for his creativity. The stark light effects give the paintings a sense of theatricality, which is heightened by some of the dynamic or unusual characters. The nature of these capricci allowed artists to indulge their artistic imaginations and produce these vibrant scenes.

A definitive attribution for the present pair of paintings remains elusive. In his 1986 monograph on Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), Ferdinando Arisi identified the pair as examples of the master’s early work, and, when considering the connection of the present pair to Panini, the depiction of the equestrian statue is particularly noteworthy. The inscription ‘SPQR’ on the pedestal of the statue means that the viewer is expected to identify the rider as a Roman emperor, and the theme of prisoners being trampled under the foot of a victorious emperor, or his horse, was enormously popular in ancient Roman iconography.¹ Most depictions of rearing equestrian statues in Italian capricci derive from a statue by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) of Louis XIV in the Guise of Marcus Curtius, which is today displayed at the Palace of Versailles. Panini used Bernini’s rearing horse motif in his depictions of Marcus Curtius, and the angle of depiction of the version in Smith College, Massachusetts, is especially comparable to that in A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue, especially in the forelegs.² It is also worth noting, whilst discussing the equestrian statue, that the captives which are being trampled probably derive from the bound prisoners at the foot of Pietro Tacca’s (1577-1640) monument to Ferdinand I de’Medici (1549-1609) in Lovorno.

The traditional attribution to Panini was questioned by David Marshall in a 2004 article. At the time Professor Marshall believed the pair to be close in style to the work of Alberto Carlieri (1672-c. 1720), and some of the figures are reminiscent of Carlieri types. For example the oriental figures in the middle ground of A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks recall a similar pair in the foreground of Carlieri’s Christ Blessing Little Children among Classical Ruins. Although Marshall now believes the link to Carlieri to be less strong³, the loose painterly technique is certainly characteristic of North Italian painting of the early eighteenth century. The flickering brushwork of the figures recalls painters working in the circle of Marco Ricci (1676-1730) or Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749), and the architecture of the present work is particularly close to the work of Magnasco’s collaborator Clemente Spera (active 1661-c. 1730). This is evident when comparing the present pair to a work such as Spera’s Landscape with Ruins and Figures, which features many of the same architectural features and motifs. This architecture is cast in a strong light which falls in a dramatic diagonal angle, in a comparable manner to the present work. Spera’s painting is similarly animated by figures which are dotted throughout the capriccio, and who at times seem to blend into the ancient landscape.

We are grateful to Professor David Marshall for his help in cataloguing the present works.

¹ For more on this theme see Mattern, S. P., Rome and the Enemy: Imperial Strategy in the Principate, (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1999) pp. 194-195.

² This is also the case, although to a lesser extent, in the version in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, no. 207.

³ Written communication, 8th March 2013.

Swiss Private Collection

Ferdinando Arisi, Gian Paolo Panini e i fasti della Roma del ‘700 (Rome, 1986), p. 221, nos. 7-8, illustrated, as early Panini;

David Marshall, ‘The Architectural Picture in 1700: The Paintings of Alberto Carlieri (1672-c. 1720), Pupil of Andrea Pozzo’,

Artibus et Historiae (50, XXV, 2004), p. 120, as ‘Not Panini, near Carlieri’.

During the early part of the eighteenth century the capricci emerged as a mature art form, the architectural fantasy serving as an ideal creative outlet for artists. This pair of paintings is indicative of the genre during that period. A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks is a dramatic image of crumbling Doric architecture. Chipped columns rise up and out of the picture, dwarfing the figures below, and a huge archway frames the background. On the right-hand side there are two monks, one of whom is engrossed in a book whilst his companion reads the inscription of the monument under which they stand. On the right-hand side two figures in oriental dress are having an intense discussion. In the background an impoverished man, slumped asleep on the ground, is contrasted with a dashing horseman, who gallops out of sight. Our eye is led from figure to figure, as the painting recedes. They animate, and draw attention to, the architectural spaces which they occupy.

A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue is in a similar setting of Roman ruins, although in this work the composition is much more spacious, with a sense of openness and a deeper internal recession. On the left-hand side is a dramatic equestrian statue, which shows a horse rearing up on its hind legs as two kneeling figures cower below. Once again, contrasting figures are scattered throughout the scene. A man in a red tunic drags a cart through the ruins and in this cart sits a legless man; the scruffy poverty of this unusual pair is contrasted with the young, elegant and well-dressed couple who stand in the shadows of the building.

Both scenes are imbued with a heavy sense of decaying antiquity. The architecture is worn and chipped by the passing of time and in A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue the huge capital of a column lies forlornly on its side. In both paintings much of the neglected architecture is overgrown with creeping foliage and in the foreground of A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks, a gnarled tree grows amongst the ancient structures. This feeling is heightened by the classical dress of some of the figures detailed.

One of the most distinctive features of this pair is the dramatic use of chiaroscuro. Both paintings are lit by bright sunshine, which makes the contrasting shadow more intense. This is particularly notable in the case of A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks, where, on the right-hand side, a thick beam of shadow slices through the bright scene. The painting anticipates the dramatic swathes of light and dark that were to characterise the capricci of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), who fully realised the genre as a vehicle for his creativity. The stark light effects give the paintings a sense of theatricality, which is heightened by some of the dynamic or unusual characters. The nature of these capricci allowed artists to indulge their artistic imaginations and produce these vibrant scenes.

A definitive attribution for the present pair of paintings remains elusive. In his 1986 monograph on Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), Ferdinando Arisi identified the pair as examples of the master’s early work, and, when considering the connection of the present pair to Panini, the depiction of the equestrian statue is particularly noteworthy. The inscription ‘SPQR’ on the pedestal of the statue means that the viewer is expected to identify the rider as a Roman emperor, and the theme of prisoners being trampled under the foot of a victorious emperor, or his horse, was enormously popular in ancient Roman iconography.¹ Most depictions of rearing equestrian statues in Italian capricci derive from a statue by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) of Louis XIV in the Guise of Marcus Curtius, which is today displayed at the Palace of Versailles. Panini used Bernini’s rearing horse motif in his depictions of Marcus Curtius, and the angle of depiction of the version in Smith College, Massachusetts, is especially comparable to that in A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with an Equestrian Statue, especially in the forelegs.² It is also worth noting, whilst discussing the equestrian statue, that the captives which are being trampled probably derive from the bound prisoners at the foot of Pietro Tacca’s (1577-1640) monument to Ferdinand I de’Medici (1549-1609) in Lovorno.

The traditional attribution to Panini was questioned by David Marshall in a 2004 article. At the time Professor Marshall believed the pair to be close in style to the work of Alberto Carlieri (1672-c. 1720), and some of the figures are reminiscent of Carlieri types. For example the oriental figures in the middle ground of A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Monks recall a similar pair in the foreground of Carlieri’s Christ Blessing Little Children among Classical Ruins. Although Marshall now believes the link to Carlieri to be less strong³, the loose painterly technique is certainly characteristic of North Italian painting of the early eighteenth century. The flickering brushwork of the figures recalls painters working in the circle of Marco Ricci (1676-1730) or Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749), and the architecture of the present work is particularly close to the work of Magnasco’s collaborator Clemente Spera (active 1661-c. 1730). This is evident when comparing the present pair to a work such as Spera’s Landscape with Ruins and Figures, which features many of the same architectural features and motifs. This architecture is cast in a strong light which falls in a dramatic diagonal angle, in a comparable manner to the present work. Spera’s painting is similarly animated by figures which are dotted throughout the capriccio, and who at times seem to blend into the ancient landscape.

We are grateful to Professor David Marshall for his help in cataloguing the present works.

¹ For more on this theme see Mattern, S. P., Rome and the Enemy: Imperial Strategy in the Principate, (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1999) pp. 194-195.

² This is also the case, although to a lesser extent, in the version in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, no. 207.

³ Written communication, 8th March 2013.

Swiss Private Collection

Ferdinando Arisi, Gian Paolo Panini e i fasti della Roma del ‘700 (Rome, 1986), p. 221, nos. 7-8, illustrated, as early Panini;

David Marshall, ‘The Architectural Picture in 1700: The Paintings of Alberto Carlieri (1672-c. 1720), Pupil of Andrea Pozzo’,

Artibus et Historiae (50, XXV, 2004), p. 120, as ‘Not Panini, near Carlieri’.

contact

contact contact

contact +44 20 7313 8040

+44 20 7313 8040