lexei Vladimirovich Issupoff

(Viatka 1889 - Rome 1957)

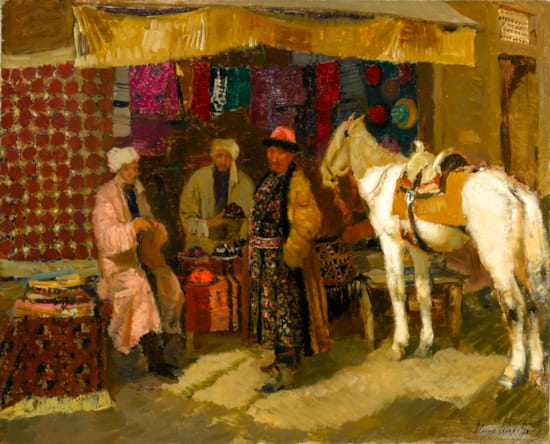

Samarkand Market

signed ‘Alessio Issupoff’ (lower right)

oil on canvas

65 x 80 cm (25½ x 31½ in)

A Kazakh well-to-do bai has come to buy a tubiteka or takiya, a flat hat often used during ceremonies, or for prayers. Richly dressed in traditional Kazakh costume, his attire and horse suggest that he is a man of means. The Uzbek merchant has a well-stocked stall with proudly displayed Bokhara carpets, korpe mattresses, that are still given as wedding presents today, and a colourful array of hats. Two of the three figures have paused their bargaining, and turned to meet the viewer’s gaze, as they calmly register our interest in the colourful exoticism of the scene. The loose rapid brush strokes which Alexei Vladimirovich Issupoff uses helps add to the sense of immediacy and of a captured moment. Issupoff was always a prolific and conscientious draughtsman throughout his life, as this medium also lent itself to achieving a sense of spontaneity. The stall is packed with goods crammed together, which merge into the shadowy recesses, suggesting an abundance of fabulous wares. Although executed predominantly in a palette of yellowish browns and reds, there significant tonal variety in the work. The variety of colour, such as vibrant pink set against deep maroon, helps evoke the bright glare and extreme heat of Samarkand.

Situated as it was along the great ‘Silk Road’, there was a lively trade of carpets in towns such as Samarkand, and the present work captures this central aspect of daily life. The Uzbekistan carpet trade, and its reputation, was such that many carpets were also exported to other countries across the world, and the importance of the design of a carpet was apparent in the eastern saying, ‘lay out your carpet, and I will see what is in your heart’. For example Bokhara carpets, which can be seen in Samarkand Market, had a design resembling the classical Bokhara pattern, which was said to be inspired by the Russians. Gül, or ‘rose’ in Persian, was the name of the most typical Bokhara motif. An octagonal circular design with slightly rounded angles, it was a recognisable motif which would be uniformly repeated across the carpet. The carpets were made by nomads, in great part by the Turkoman tribe of the Tekkeh who lived on the Trans-Caspian steppes. Bokhara carpets which were known for their high quality wool and for being hard wearing, and had a rough red base.

Before the present work was painted there was a established tradition in Russia of recording the alien exoticism of Samarkand. The Russian empire was so vast that there was a natural interest in Western Russia into the cultural diversity that could be found across the Empire. As one of the great cities of Central Asia, Samarkand was the subject of much of this interest. Perhaps the best example of this cultural phenomenon is the work of the photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944). In the early 1900s, and with the support of Tsar Nicholas II, Prokudin-Gorskii formulated a plan to document the Russian Empire and with a specially equipped railroad car, fitted with a darkroom, he accessed areas of the Empire that had been restricted, completing surveys of eleven regions between 1909 and 1912, and again in 1915. He created a varied visual record of the Russian Empire at its peak, photographing and capturing its people, culture, architecture, landscape and scenery, from the Caucasus to Central Asia, including nearly 170 images of Samarkand alone. It is in the same spirit of ethnographic interest that Issupoff painted the present work, which is comparable, in the wonderful display of brightly coloured hats and splendid array of materials and carpets that the Uzbek merchant has on offer, to Prokudin-Gorskii’s Fabric Merchants in the Registan Samarkand. Samarkand Market is a direct testimony to Issupoff’s own fascination with the cultural climate of Central Asia. However it goes a step beyond the substantial body of photographs of Samarkand that Gorskii produced, by truly bringing to life the colours and existence of the city.

Samarkand Market comes from the three year period, from 1918-1921, when Issupoff was living and working in Central Asia, a period which was hugely important in his development as an artist, and during this time he produced some of his most iconic works. Many years later, when discussing his work, his wife, Tamara Nikolaevna, remarked, “Turkestan was a wonderful place of Isupov’s true art. As an artist of the Russian school, he found there everything that he was looking for: the light the sun, the shadows... He became a brilliant, unparalleled creator of poetry, hues, and colours...”.¹ Issupoff’s work in Samarkand examined all aspects of the city, from depictions of some of the city’s great historical sites, such as Tilya-Kori Madrasah in Samarkand, (Private Collection) to studies of the humbler, everyday lives of the Usbek people. Studies of Issupoff’s work in this period are aided by the fact that he reworked many of his compositions into a series of colour postcards, entitled Turkestan in the paintings of A. Isupoff, which were published in 1929, an example of which is Oriental Blacksmith. Tilya-Kori Madrasah in Samarkand is perhaps a more traditional vision of Samarkand; a distanced grandiose depiction of magnificent architecture, colourful throngs of people and an evocation of the intense dusty heat of the city. Although this panoramic view is very different in composition to the focused Samarkand Market, both works are concerned with the strange and fascinating culture of Uzbekistan, which would have been so alien to the Issupoff’s audience in the more European corners of the Russian Empire.

Oriental Blacksmith is, like the present work, a more studied work, depicting just a few figures, and examining aspects such as the cloths and habits of Issupoff’s subjects. One of the most distinctive characteristics of both works, however, is Issupoff’s ability to capture the bright glare of the city’s white sunlight. His ability to render this, and his fascination with the resultant contrasts of light and shade, is evident in both works. This particular fascination with light had been evident in some of Issupoff’s earliest works, such as Teahouse, which although executed in a much more controlled fashion than Samarkand Market, is flooded with the same intense light.

Issupoff was born in Vyatka (now Kirov) into the family of a master iconostasis maker, and his first teachers were icon painters. Under the influence of another local artist, the already renowned painter Apollinary Mikhailovich Vasnetsov, his art started to develop a more independent streak, and his work began to appear in the first Vyatkan art exhibitions. As a result of this initial success Issupoff decided to move to Moscow to study, although he had sell sketches to fund the trip, as his parents weren’t able to financially support him. In 1908 he enrolled in the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and again came to the attention of Vasnetsov, who, although some thirty years Issupoff’s senior and at the height of his career, recognised the young man’s talent and introduced him into his artistic circle. Vasnetsov “would invite the young man for a cup of tea – to pass evening hours in talks about art... those were like evening classes in art history...”.² Issupoff flourished in Moscow, through either direct contact with teachers such as Vasnetsov and Konstantin Alekseyevich Korovin (1861-1939), or through exhibitions, where he encountered the work of Philip Andreyevich Maliavian, whose use of light and colour was to prove extremely influential. By the time he graduated in 1912, Issupoff’s was already demonstrating his ability to capture an atmosphere, a skill evident in Samarkand Market.

Issupoff first visited Central Asia when he was sent to Tashkent in 1915 as part of his military service. Although he returned to Moscow two years later, having been discharged due to ill health, he returned to Uzbekistan as soon as possible with his wife. Irina Lyubimova surmises his the development in his work of this period, which includes Samarkand Market, saying “By studying various ethnic types – their everyday life, clothes, and household effects – he broadened the thematic range of his paintings. Isupov depicted noisy markets, teahouse, blacksmith shops, street scenes, and architectural landmarks. His palette also grew richer...The artist paints landscapes in brief quick brushstrokes that create the effect of vibrating air, light and colour, and he achieves a sense of luminous overtones.”³ During his time in Central Asia he also became director of the Art Department in the Committee of Restoration and Protection of Monuments in the City of Samarkand, a role that allowed him to truly immerse himself in the city’s cultural history.

In 1921 Issupoff returned to Moscow but struggled both financially, and to commit himself to do work for the new Soviet state. After five difficult years he left for Italy on doctors’ recommendations and here he artistically flourished once again. His art still remained rooted in his homeland, with Russian references and motifs populating his work, and it was known that he longed to return home, although he never did. He found it especially difficult during World War II, living under a Fascist regime and he actively helped the resistance. Despite this he was a critical and commercial success in his adopted country, praised for his “wide brushstroke, fine detail, striving towards the truth” and “gentleness of colour”.⁴ He died in Rome in 1957 and was buried alongside other Russian artists, including Karl Pavlovich Bryullov.

¹ Letter from Tamara Nikolaevna Isupova to V. N. Moskvinov, July 7th 1964.

² Vasnetsov, Vsevolod Apollinarievich, Pages of the Past (Leningrad, 1976), p. 18.

³ Lyubimova, Irina, ‘Alexei Isupov: Between Russia and Italy’, in The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine (no. 2, 2009, vol, 23), pp.20&22.

⁴ Ibid. cited, p. 26.

A Kazakh well-to-do bai has come to buy a tubiteka or takiya, a flat hat often used during ceremonies, or for prayers. Richly dressed in traditional Kazakh costume, his attire and horse suggest that he is a man of means. The Uzbek merchant has a well-stocked stall with proudly displayed Bokhara carpets, korpe mattresses, that are still given as wedding presents today, and a colourful array of hats. Two of the three figures have paused their bargaining, and turned to meet the viewer’s gaze, as they calmly register our interest in the colourful exoticism of the scene. The loose rapid brush strokes which Alexei Vladimirovich Issupoff uses helps add to the sense of immediacy and of a captured moment. Issupoff was always a prolific and conscientious draughtsman throughout his life, as this medium also lent itself to achieving a sense of spontaneity. The stall is packed with goods crammed together, which merge into the shadowy recesses, suggesting an abundance of fabulous wares. Although executed predominantly in a palette of yellowish browns and reds, there significant tonal variety in the work. The variety of colour, such as vibrant pink set against deep maroon, helps evoke the bright glare and extreme heat of Samarkand.

Situated as it was along the great ‘Silk Road’, there was a lively trade of carpets in towns such as Samarkand, and the present work captures this central aspect of daily life. The Uzbekistan carpet trade, and its reputation, was such that many carpets were also exported to other countries across the world, and the importance of the design of a carpet was apparent in the eastern saying, ‘lay out your carpet, and I will see what is in your heart’. For example Bokhara carpets, which can be seen in Samarkand Market, had a design resembling the classical Bokhara pattern, which was said to be inspired by the Russians. Gül, or ‘rose’ in Persian, was the name of the most typical Bokhara motif. An octagonal circular design with slightly rounded angles, it was a recognisable motif which would be uniformly repeated across the carpet. The carpets were made by nomads, in great part by the Turkoman tribe of the Tekkeh who lived on the Trans-Caspian steppes. Bokhara carpets which were known for their high quality wool and for being hard wearing, and had a rough red base.

Before the present work was painted there was a established tradition in Russia of recording the alien exoticism of Samarkand. The Russian empire was so vast that there was a natural interest in Western Russia into the cultural diversity that could be found across the Empire. As one of the great cities of Central Asia, Samarkand was the subject of much of this interest. Perhaps the best example of this cultural phenomenon is the work of the photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944). In the early 1900s, and with the support of Tsar Nicholas II, Prokudin-Gorskii formulated a plan to document the Russian Empire and with a specially equipped railroad car, fitted with a darkroom, he accessed areas of the Empire that had been restricted, completing surveys of eleven regions between 1909 and 1912, and again in 1915. He created a varied visual record of the Russian Empire at its peak, photographing and capturing its people, culture, architecture, landscape and scenery, from the Caucasus to Central Asia, including nearly 170 images of Samarkand alone. It is in the same spirit of ethnographic interest that Issupoff painted the present work, which is comparable, in the wonderful display of brightly coloured hats and splendid array of materials and carpets that the Uzbek merchant has on offer, to Prokudin-Gorskii’s Fabric Merchants in the Registan Samarkand. Samarkand Market is a direct testimony to Issupoff’s own fascination with the cultural climate of Central Asia. However it goes a step beyond the substantial body of photographs of Samarkand that Gorskii produced, by truly bringing to life the colours and existence of the city.

Samarkand Market comes from the three year period, from 1918-1921, when Issupoff was living and working in Central Asia, a period which was hugely important in his development as an artist, and during this time he produced some of his most iconic works. Many years later, when discussing his work, his wife, Tamara Nikolaevna, remarked, “Turkestan was a wonderful place of Isupov’s true art. As an artist of the Russian school, he found there everything that he was looking for: the light the sun, the shadows... He became a brilliant, unparalleled creator of poetry, hues, and colours...”.¹ Issupoff’s work in Samarkand examined all aspects of the city, from depictions of some of the city’s great historical sites, such as Tilya-Kori Madrasah in Samarkand, (Private Collection) to studies of the humbler, everyday lives of the Usbek people. Studies of Issupoff’s work in this period are aided by the fact that he reworked many of his compositions into a series of colour postcards, entitled Turkestan in the paintings of A. Isupoff, which were published in 1929, an example of which is Oriental Blacksmith. Tilya-Kori Madrasah in Samarkand is perhaps a more traditional vision of Samarkand; a distanced grandiose depiction of magnificent architecture, colourful throngs of people and an evocation of the intense dusty heat of the city. Although this panoramic view is very different in composition to the focused Samarkand Market, both works are concerned with the strange and fascinating culture of Uzbekistan, which would have been so alien to the Issupoff’s audience in the more European corners of the Russian Empire.

Oriental Blacksmith is, like the present work, a more studied work, depicting just a few figures, and examining aspects such as the cloths and habits of Issupoff’s subjects. One of the most distinctive characteristics of both works, however, is Issupoff’s ability to capture the bright glare of the city’s white sunlight. His ability to render this, and his fascination with the resultant contrasts of light and shade, is evident in both works. This particular fascination with light had been evident in some of Issupoff’s earliest works, such as Teahouse, which although executed in a much more controlled fashion than Samarkand Market, is flooded with the same intense light.

Issupoff was born in Vyatka (now Kirov) into the family of a master iconostasis maker, and his first teachers were icon painters. Under the influence of another local artist, the already renowned painter Apollinary Mikhailovich Vasnetsov, his art started to develop a more independent streak, and his work began to appear in the first Vyatkan art exhibitions. As a result of this initial success Issupoff decided to move to Moscow to study, although he had sell sketches to fund the trip, as his parents weren’t able to financially support him. In 1908 he enrolled in the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and again came to the attention of Vasnetsov, who, although some thirty years Issupoff’s senior and at the height of his career, recognised the young man’s talent and introduced him into his artistic circle. Vasnetsov “would invite the young man for a cup of tea – to pass evening hours in talks about art... those were like evening classes in art history...”.² Issupoff flourished in Moscow, through either direct contact with teachers such as Vasnetsov and Konstantin Alekseyevich Korovin (1861-1939), or through exhibitions, where he encountered the work of Philip Andreyevich Maliavian, whose use of light and colour was to prove extremely influential. By the time he graduated in 1912, Issupoff’s was already demonstrating his ability to capture an atmosphere, a skill evident in Samarkand Market.

Issupoff first visited Central Asia when he was sent to Tashkent in 1915 as part of his military service. Although he returned to Moscow two years later, having been discharged due to ill health, he returned to Uzbekistan as soon as possible with his wife. Irina Lyubimova surmises his the development in his work of this period, which includes Samarkand Market, saying “By studying various ethnic types – their everyday life, clothes, and household effects – he broadened the thematic range of his paintings. Isupov depicted noisy markets, teahouse, blacksmith shops, street scenes, and architectural landmarks. His palette also grew richer...The artist paints landscapes in brief quick brushstrokes that create the effect of vibrating air, light and colour, and he achieves a sense of luminous overtones.”³ During his time in Central Asia he also became director of the Art Department in the Committee of Restoration and Protection of Monuments in the City of Samarkand, a role that allowed him to truly immerse himself in the city’s cultural history.

In 1921 Issupoff returned to Moscow but struggled both financially, and to commit himself to do work for the new Soviet state. After five difficult years he left for Italy on doctors’ recommendations and here he artistically flourished once again. His art still remained rooted in his homeland, with Russian references and motifs populating his work, and it was known that he longed to return home, although he never did. He found it especially difficult during World War II, living under a Fascist regime and he actively helped the resistance. Despite this he was a critical and commercial success in his adopted country, praised for his “wide brushstroke, fine detail, striving towards the truth” and “gentleness of colour”.⁴ He died in Rome in 1957 and was buried alongside other Russian artists, including Karl Pavlovich Bryullov.

¹ Letter from Tamara Nikolaevna Isupova to V. N. Moskvinov, July 7th 1964.

² Vasnetsov, Vsevolod Apollinarievich, Pages of the Past (Leningrad, 1976), p. 18.

³ Lyubimova, Irina, ‘Alexei Isupov: Between Russia and Italy’, in The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine (no. 2, 2009, vol, 23), pp.20&22.

⁴ Ibid. cited, p. 26.

contact

contact contact

contact +44 20 7313 8040

+44 20 7313 8040