lexei Alekseevich Harlamoff

(Saratov 1840 - Paris 1922)

Portrait of a Young Woman

signed ‘Harlamoff’ (lower left)

charcoal on paper

51 x 37 cm (20 x 14½ in)

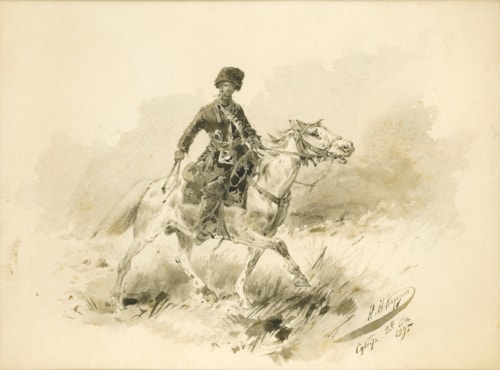

In this exquisite charcoal drawing a young girl casts her eyes down, shyly avoiding the viewer’s gaze. She clutches her right hand to her heart, holding her shawl tight to her chest. Her hair is tied loosely at the top of her head, and a few strands fall framing her face. Alexei Alekseevich Harlamoff smudges the extremes of the subject, such as her hair and shawl, so that we are instantly drawn to the girl’s face and full lips. The lines of the charcoal and the way they flow to create the most intricate features indicate the agility and expertise of Harlamoff’s draughtsmanship.

Portrait of a Young Woman is a fine example of Harlamoff’s characteristic, informal executions of idealised girls and young women. Harlamoff worked prolifically throughout his lifetime and the present drawing is comparable to many of his works. The slightly coy and withdrawn character of the sitter in the present drawing is found in many of his works, for example Head of a Young Girl (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). In both cases the sitters seem bashful, holding their hands to their chests slightly defensively: Harlamoff has thus presented images of modest beauty. Harlamoff’s technical skill is evident in his modelling of light and his soft, careful and delicate handling in the depiction of the sitters’ faces.

Harlamoff produced numerous portraits of this type but although they invariably share the quality of idealised beauty, there is great variety in the personalities of his young sitters. He often used flowers to symbolise their innocence and the fragility of youth, and always retained a wholly Russian feel to them, through their facial features or dress. Harlamoff was not concerned with producing accurate portraits, rather he was fascinated with the aesthetic impact. His brilliance was is in bringing out the sitter’s natural beauty and getting them to immediately engage with the viewer through a range of emotions.

Harlamoff was born in Russia and, having excelled at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, he moved to Paris in 1869, where he spent most of his life. Here he was taught by Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), one of the leading French artists of the day, famed for his portraits, who was to have a profound influence on Harlamoff’s work. He started to exhibit regularly throughout the 1870s, and gained great critical acclaim; his portraits were praised by Emile Zola (1840-1902) as some of the best work of the 1875 Salon.

In 1880 Harlamoff was accepted as a full member of the Association of Itinerant Art Exhibitions, the most progressive and influential artistic group in Russia in the second half of the nineteenth century. Yet despite this membership his ‘art was more appreciated in Europe than in Russia,’ as Harlamoff was criticised in his homeland for his subject matter, which was said to show an indifference to the problems of Russian society.¹ In contrast his work was well received in Western Europe because it demonstrated such talent and skill and such a focus on beauty charmed many viewers, including Queen Victoria (1819-1901) who admired his work at the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888.

¹ Sugrobova-Roth, O. & Lingenauber, E., Alexei Harlamoff: Catalogue Raisonné (Düsseldorf, 2007), p. 7.

Doyle New York, European and American Paintings and Sculpture, 4 May 1995, lot 13

Private collection, USA

O. Sugrobova-Roth and E. Lingenauber (Eds.), Alexei Harlamoff: catalogue raisonné., Düsseldorf: Editions A.Harlamoff, 2007, p.286, No.326, illustrated pl.276

In this exquisite charcoal drawing a young girl casts her eyes down, shyly avoiding the viewer’s gaze. She clutches her right hand to her heart, holding her shawl tight to her chest. Her hair is tied loosely at the top of her head, and a few strands fall framing her face. Alexei Alekseevich Harlamoff smudges the extremes of the subject, such as her hair and shawl, so that we are instantly drawn to the girl’s face and full lips. The lines of the charcoal and the way they flow to create the most intricate features indicate the agility and expertise of Harlamoff’s draughtsmanship.

Portrait of a Young Woman is a fine example of Harlamoff’s characteristic, informal executions of idealised girls and young women. Harlamoff worked prolifically throughout his lifetime and the present drawing is comparable to many of his works. The slightly coy and withdrawn character of the sitter in the present drawing is found in many of his works, for example Head of a Young Girl (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). In both cases the sitters seem bashful, holding their hands to their chests slightly defensively: Harlamoff has thus presented images of modest beauty. Harlamoff’s technical skill is evident in his modelling of light and his soft, careful and delicate handling in the depiction of the sitters’ faces.

Harlamoff produced numerous portraits of this type but although they invariably share the quality of idealised beauty, there is great variety in the personalities of his young sitters. He often used flowers to symbolise their innocence and the fragility of youth, and always retained a wholly Russian feel to them, through their facial features or dress. Harlamoff was not concerned with producing accurate portraits, rather he was fascinated with the aesthetic impact. His brilliance was is in bringing out the sitter’s natural beauty and getting them to immediately engage with the viewer through a range of emotions.

Harlamoff was born in Russia and, having excelled at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, he moved to Paris in 1869, where he spent most of his life. Here he was taught by Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), one of the leading French artists of the day, famed for his portraits, who was to have a profound influence on Harlamoff’s work. He started to exhibit regularly throughout the 1870s, and gained great critical acclaim; his portraits were praised by Emile Zola (1840-1902) as some of the best work of the 1875 Salon.

In 1880 Harlamoff was accepted as a full member of the Association of Itinerant Art Exhibitions, the most progressive and influential artistic group in Russia in the second half of the nineteenth century. Yet despite this membership his ‘art was more appreciated in Europe than in Russia,’ as Harlamoff was criticised in his homeland for his subject matter, which was said to show an indifference to the problems of Russian society.¹ In contrast his work was well received in Western Europe because it demonstrated such talent and skill and such a focus on beauty charmed many viewers, including Queen Victoria (1819-1901) who admired his work at the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888.

¹ Sugrobova-Roth, O. & Lingenauber, E., Alexei Harlamoff: Catalogue Raisonné (Düsseldorf, 2007), p. 7.

Doyle New York, European and American Paintings and Sculpture, 4 May 1995, lot 13

Private collection, USA

O. Sugrobova-Roth and E. Lingenauber (Eds.), Alexei Harlamoff: catalogue raisonné., Düsseldorf: Editions A.Harlamoff, 2007, p.286, No.326, illustrated pl.276

contact

contact contact

contact +44 20 7313 8040

+44 20 7313 8040